"Time and Transcendence - as reflected in the philosophical art of Roland van den Berghe"

by Avraham 'Pachi' Shapira (University of Tel Aviv)

Woord vooraf: onderstaande tekst is een transcript op basis van een OCR-scan van het papieren, getypte origineel (d.d. 1992). Sommige letters, woorden en zinsdelen zijn daarbij weggevallen en (waar gezien) met de hand gecorrigeerd en teruggeschreven. Download het .pdf-bestand voor het complete origineel.

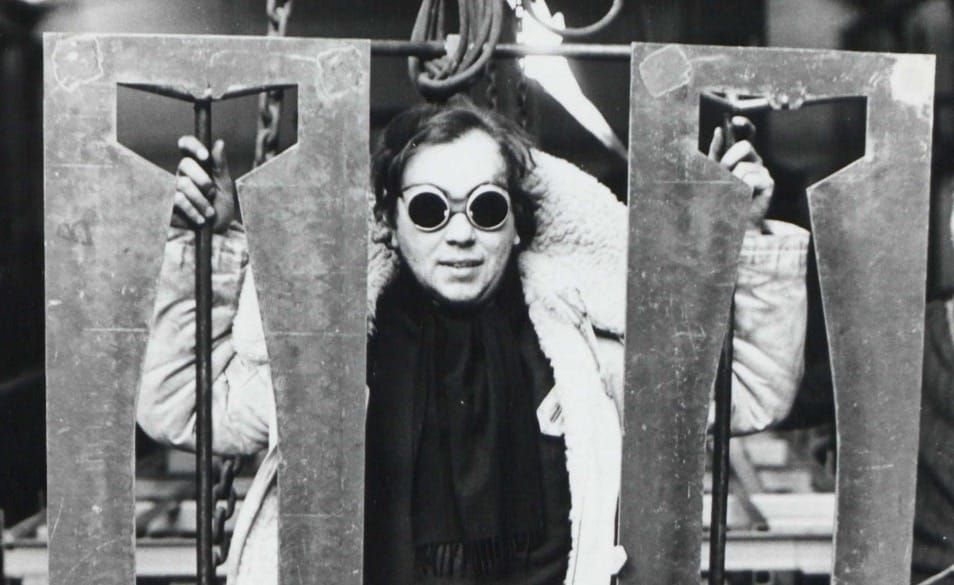

For the last twenty-five years Roland van den Berghe has made Amsterdam the centre and base of his artistic activities. Although Van den Berghe (Ghent 1943) is Flemish by birth, his conceptual world oversteps the formal boundaries of national and ethnic identity (1). He is indisputably an artist of European dimensions.

However, his work — as is often the case with great art — forms a rich carpet, woven from various sources and cultures, thereby acquiring a certain depth and versatility. His main projects have germinated on fertile but very different foundations, which bear witness to the fact that he possesses a broad personality and a wide horizon. The distance between the soils he has cultivated may be as far as the East Coast of the United States is from the West Coast, or the Socialist Republic of Vietnam from the land of Israel. In the TIsrael project which will be discussed here we can see the intertwining of both Jewish and Israeli motifs.

The mere indication of the confluence of themes and content in Van den Berghe's work fails to do it justice, because it is just as multidisciplinary in the sense that divergent methods and forms of expression meet in it. His work cuts across different artistic disciplines: the visual resources of the painter, the sculptor and the photographer are combined, while none of these three is the exclusive focus of attention. These facets are relevant for his work because they grow in the artist as an organic unity. The term “organic' here refers to a complete entity that is always more than the sum of its parts and in which every facet illuminates and is illuminated by the existence of the others. Anyone wanting to explain this exceptional combination of artistic idioms and talents must penetrate to the depths of the artist himself, to the quarry of his creative mind, which show him to be not only the artist that he already is, but even more a philosophical inquirer. The compass by which he works — and this is particularly clear in the case of the most ambitious projects — could be described as something formed in the deepest recesses of his thoughts, where the visible and the invisible are one in the prenatal stages of creativity, hidden in the innermost person of the artist.

The idea of a ‘combination of all arts' is often written off as wishful thinking, but this wish is nevertheless fulfilled to a certain degree in Van den Berghe's work.

With regard to the Chinese, one may wonder to what extent they ‘draw' their words, and to what extent their calligraphy is based on an abstraction of letter and word. But there is no need to raise questions of this kind in the context of Roland van den Berghe's multidisciplinary work. His art not only combines the different areas of artistic creativity, but it also associates them with ideas that extend further. Philosophical structures and colourful poetry interact with one another — message and sensation meet and intertwine.

I. The Fabiola project (Brussels 1969)

One of the places where this work was displayed was the exhibition “Aspects of contemporary art in Belgium (Antwerp International Cultural Centre 1974). The art critic Barbara Reise wrote: (...) Roland Van den Berghe, who lives in Amsterdam and New York, presented his projects of peoples' participatory colouring of Queen Fabiola and the Belgian cyclist Eddy Merckx (...). With an invitation to all readers to add colour without inhibitions, a drawing of Fabiola had been published in the Flemish television magazine HUMO on 25 March 1971 and one of Eddy Merckx in the French-Belgian review Special on 12 January 1972. Some of the works sent back to the artist through the magazines were exhibited on a table, on the surrounding walls were exhibited six series of seven different drawings of Fabiola and Merckx which had been submitted to people of the renown of the Marxist economist Ernst Mandel (who wrote a treatise across the set of drawings), the poet Marcel Van Maele (whose differently cubistically-coloured drawings were in the row above) and the cartoonist Gal who made imaginative collages on the set. And I think the association of famous Belgians's images, however politically controversial, is far less important in this work than is the very effective creation of a network in which 'art' and 'ordinary people' - as well as ‘extraordinary people' - can actually and directly participate. It is not only the only work I saw in Belgium which achieved this, it is also the work which has most thoroughly structured this important relationship which I have seen any place.(2)"

One of the more unpleasant consequences of this project for Van den Berghe himself was a period in prison.

II. The first project in New York (1972-1974)

This project consisted of various components:

1. Guernica action, Museum of Modern Art (New York 12 July 1972)

2. A step for step carpet (New York-Amsterdam 1972).

The catalogue: "(...) In the phase "Our friendly bombs", sheets of cardboard, each 100 x 100 cms, were stuck to the road with tape in various parts of New York, e.g. in Down Town East or under the escalators of the Grand Central station. Between the road and cardboard is a piece of canvas also measuring 100 x 100 cms. The outline of a bomb has been cut out of the corrugated cardboard. This outline, under which the canvas is visible, is coated with Mixtion, a glue which is also used for frescoes and which retains its adhesive properties for 12 hours. As people walk over it footprints are left on the canvas with the dust from the streets of New York. The corrugated cardboard is then removed from the canvas leaving the bomb painting. In this way anonymous people take part more or less unconsciously in the production of missiles and destructive weapons. It is this "Enlightment"” function over and against the anonymous forces in our society which is of such importance in all V.d.B's activities. (...)

The bomb rug is on exhibition in an annex of the Whitney Museum in New York. Peggy Guggenheim's son-in-law provided the "veneer" by ripping and tearing the canvas so that the bombs have as it were exploded. (...) This American bomb rug, consisting of 50 paintings joined, hung in Paradiso Amsterdam, in 1972. The evening that the results of Nixon's re-election as President of the United States were broadcast on T.V. Van den Berghe laid an European bomb rug of 50 paintings on the ground. The rug was danced on, walked on and people watched television on it. At the end of the evening the part lying on the floor, in the shape of the 50 stars like on the American flag, was raised on one side until it formed an angle of 70 degrees with the American rug hanging on the wall. (...) At this exhibition in the Hedendaagse Kunst 50 American and 50 European bomb paintings are exhibited.

3. Change of address: two new galoshes for a president (Strasbourg—Washington-Geneva 18 January 1973).

4. Our Friendly ‘Boomerang' — Their Friendly ‘Miss Europe', a pack of playing cards (New York-Amsterdam 1974).

"(...) A new technique for your personal playing cards: The Belgian artist Roland Van den Berghe has developed an entirely new and fascinating technique for the production of your personal playing cards. Julius Rosenblum, President of the World Bridge Federation was so enchanted with the idea that he has already had a twin pack prepared for himself, On the backs of one pack of what are otherwise quite normal playing cards there are fifty-three different photographs - street scenes - buildings - studies of people, and so on.

The backs of the cards of the other pack are left blank - until you decide what you would like printed on them. You can have your own portrait, photographs from the 0lympiad as a souvenir, or what you will... (4)"

III. Otterlo, eleven bicycles - one trowel (1977)

"(...) In 1974 Roland Van den Berghe first combined 11 bicycles, which had been used on the Ho-Chi-Min route during the Vietnam War, converted to transport bicycles, and which can be seen as the symbol of Vietnamese resistance; they bear a small red trowel. This was something Roland Van den Berghe repeated in Otterlo, where the 11 bicycles were confronted with Oldenburg's huge trowel in three different arrangements (5)”

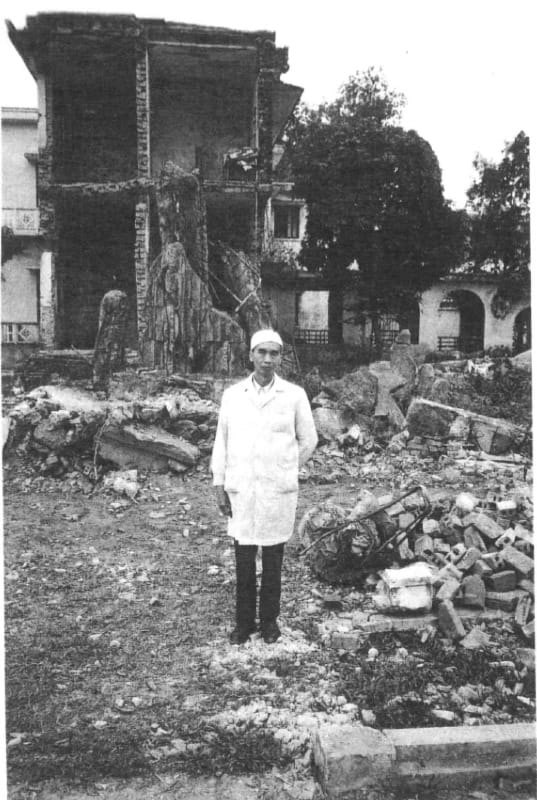

IV. The Vietnam project - 36 exposures (1979)

This work is based on a series of photographs on location. Willem Elias wrote the following when this work was exhibited in the Free University Brussels in 1990.

"(...) These images have in common the fact that they were made in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and that each of them features a crutch. The crutch is here a symbol: the reverse of the decoration for courage. The warning that these images are not photographs is highly suggestive While the motto ‘This is not a pipe’ betrays the image by pointing to its lack of reality, the effect of ‘This is not a photograph' is the opposite: it is not an image; it is reality — the violence of the War-Might Apparatus. It also has something else to say. Van den Berghe breaks wi th the history of photography. He is not an amateurish, unprofessional user of Light-capture (36 exposures). He is not a tourist locking for souvenirs; not an aesthete who wants to print artistic photographs; not a reporter who wants to illustrate a story; nor even a social photographer who wants to denounce shocking situations. He just constructs mental images.

This series of mental images is an example of two concepts in Michel Foucault's philosophy of art: heterotopy, and counter-discourse. The crutch as a constant eyesore to the beholder is a heterotopy. According to Foucault, this is a text or image that is disturbing because it undermines language, prevents things from being named, jumbles up correspondences, and mangles coherence. Foucault prefers this to the utopia which, as a non-existent dream-world, dces not take on any disruptive form. In this sense, the oeuvre of Roland Van den Berghe is still a counter- discourse, a constantly recalcitrant reaction to what the world around him (the marriage of Christianity and capitalism) would like us to believe, as well as to the forms which his colleagues give to their reaction, whether pro or con. With art against the world, against art, for the world, for art.”

V. The Israel project (1988-1993). Concept and working hypothesis: ‘Grafting with a budding scion'

The original skeleton of this project is formed by a series of colour photographs which Van den Berghe took in Israel. The photographs zigzag over the country, from North to South and from East to West. They take in the Golan Heights, the mountains near Nazareth and the valley of Yizreel, they continue their journey to the hills of Judea and to Jerusalem before plunging down into the basin of the Dead Sea and its surroundings (whre the famous scrolls are hidden), and finally exploring the secrets of the Negev desert. All of these photographs have one striking feature in common: the presence of a soap-bubble, shining and glittering like an enormous jewel in the centre of the picture. The representation is entirely dominated by this radiating sphere, which looks like a self-contained mini-universe and captures the viewer's gaze.

The execution of the project itself occupied a number of weeks, but the artist spent two long years in preparing it. Despite his being permeated by the reality of Western Europe, this protracted period of preparation must have enabled him to submerge in the spirit and atmosphere of Israel, to allow himself to be overrun by the spirit and mentality of the country and its people. His aim was t¢ arrive at a poetic vision of the country, and the result certainly is astounding. It shows that Roland van den Berghe has an exceptional capacity to capture the external and visible messages of the Israeli landscape, and at the same time to take note of the layers hidden within it. It is as if a plumb-line is lowered into the depths of the Holy Land.

This capacity — to react not only to what is visible to the untrained eye but also to what only reveals itself to the inspired eye — is undoubtedly the most important task of an artist. Artists are by nature those who are best equipped to fulfil this task and to bridge the gap between the subjective and the objective. After all, we could add, artists are by definition never satisfied with the analytical approach, which always implies a distance between the viewer and the viewed. On the contrary, artists try to get to the bottom of what is viewed. They try to overcome the objectifying point of view of science and inquiry by deploying different means of communication and thereby getting closer to the object. In Roland van den Berghe's Israel project, this approach to the object is achieved through the camera, whose lens has become an extension of the artist himself. For him, the camera more than an instrument that he has put at the service his artistic intuition. The term “intuition" is used here in the sense that Buber gave to it: "a bold swinging, demanding the most intensive stirring of one's being into the life of the other". And the ‘other' is what confirms our own ‘wholeness, unity and unicity (8), Buber tells us.

Buber elaborates this notion of intuition by claiming that it is the “"sympathy through which one transposes oneself into the interior of an object" (9). This ability — the capacity to transform the visual field into something that still has to be discovered, a process which our artist has applied to the Israeli landscape — is defined by Buber as “the decisive element that makes something a work of art'. Buber points out that it is not just a guestion of the ‘perception of a being' that lies hidden deep in matter, but of "an ever renewed vital contact with it in which the experience of the senses only fits in as a factor. of course one cannot say of this contact that it is reflected or displayed in the work - The artist does not hold a fragment of being up to the light; he receives from his contact with being and brings forth what has never before existed. It is essentially the same with the genuine philosopher, only here a great consciousness is at work that wills tP bring forth nothing less than a symbol of the whole" (10).

Buber here seems to offer us a key to the decipherment of the relations between the artist and the philosopher. They are both familiar with total dedication to the creation of something new, and in both cases this work of creation is the product of a genuine encounter in which self and other are vitally involved.

Alfred North Whitehead investigates the relations between art and philosophy from a different perspective. Poetry, he claims, comes to the aid of philosophy by proffering one of the most essential forms of perception, namely intuition. If the decisive role of philosophy really does lie in the “completion of abstraction', it will certainly resort to ‘the ‘more concrete and intuitive relation tfl the universe', in other words, to the ‘poet's testimony' (11).

In spite of Whitehead's acute observation, it is rare to come across philosophers who really possess the capacity to enrich their vision with the assistance of the penetrating intuitions of the artist. All the same, Whitehead's conception of the necessary influence of art on philosophy provides us with a principal yardstick by which to assess Van Den Berghe in his capacity as artist- philosopher.

The coexistence of the poet and the philosopher in the art and personality of Roland van de Berghe calls for further examination. As I have said, the way in which he expresses himself poetically and artistically extends beyond the contours lent by colour and form. We should bear in min that this form of expression is equally formed by a personal credo, in other words by the spiritual reflections and vision of the philosopher that he undoubtedly is. However, we may wonder whether these two spheres really are intertwined in a balanced way, or whether they perhaps represent two isolated fields whi h vie with one another for the artist's attention. For example, are there traces in his texts or visual work which point to the need or the challenge to bridge the gap which seems to exist between the personal urge to artistic creation, on the one hand, and the more philosophical style of reflection or interpretation, on the other?

Questions of this kind were also raised in discussions of the work of the artist René Magritte. He was well awars the fact that a battle raged inside him between the natural talent to express himself in colour and form, on the one hand, and his tendency to privilege the field oF philosophy and thought, on the other. It has been sai him that "He disliked being called an artist, prefe ring to be considered a thinker who communicated by means of paint. While many painters whose work holds philosophical implications are not self-consciously involved with "ideas", Magritte read widely in philosophy and listed among his favourite authors Hegel , Martin Heidegger, Jean Paul Sartre - and Michel Foucault" (12).

His famous work ‘Ceci n'est pas une pipe' is a telling example of Magritte's attitude toward art (13).

In various ways, Van den Berghe's work offers us a possible rejoinder to these guestions. It can be said th his metaphysical ideas — and perhaps one should even re to his theological ideas — are fused with his view of art These two dimensions of his world are blended in a comprehensive ontological process. They form the organic unity which is a permanent feature of his creative production (14). The ingenious way in which Van den Berghe uses bubbles in the Israel project shows us how his fanciful, poetic vision and his philosophical penchant react to one another. It becomes a vehicle by which to tackle the qguestion of time and eternity. The combination of an undoubtedly particular view of the country {even though il is the Holy Land) in the reflection of a bubble — suspended motionless in the air — offers a philesophical and artistic response to one of the recurring questions of human life: how is one to hold on to the rare moments of intensively experienced ecstasy?

There is yet another distinctive feature of Van den Berghe's artistic endeavour: the fact that it is sustained both by the Zeitgeist and by timeless human ideals, ideals which have been stripped of their Jewish and Hellenic origin now represent the classic al heritage of Western humanism. In Van den Berghe's work the mental and mate domains overlap and merge. One has only to refer to the theme of ‘culture as activity', culture as a sea ing commitment in which the forces of belief, morality and utopia are united. Van den Berghe's art is thoroughly saturated by the complexity of this view of the wor wrestles with the problems of human existence and find ways of representing them. He sets himself the taskof creating a visual world in which reality is reflected. But his task is much more than that: he also tries to find solutions by tackling the problems of existence from a compelling moral code, based on a believe in the capacity to improve and perfect the world.

Roland van den Berghe gives form to his vision on the basis of a lively dialogue with the reality of our world. He is interested not only in the problems and suffering of individual people, but also in the stumbling-blocks which so hamper human existence in the confusion of the contemporary world. He does not shy away from the ma j social ideas, nor is he afraid of political confronta All the same, he tries to strip both of these elements of their historical limitations, of the rhythm of events as it is presented every day in the flood of headlines. He describes and distinguishes the essence that is concealed within the outer garment, and distils what “ought to be' from what ‘is'. Van den Berghe's creative work is thus marked by a confluence of ‘Augenblick' and “Ewigkeit'. This fundamental quality of his oeuvre is pre-eminently present in his Israel project.

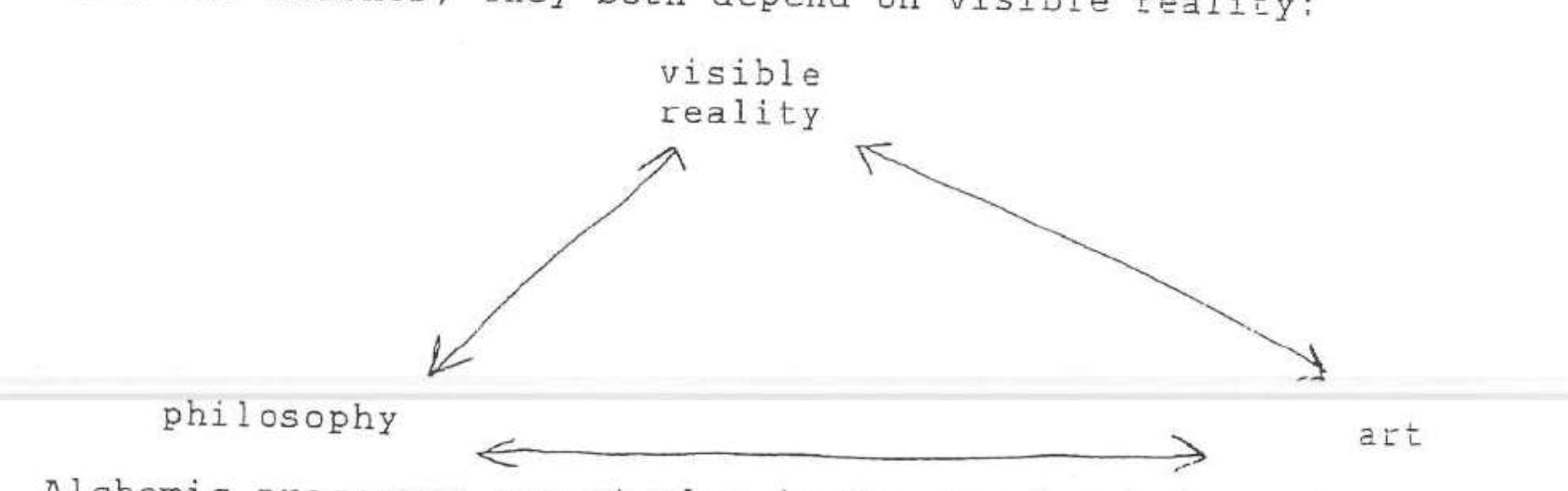

We can now proceed on the basis of a triangular model the relations in the work of Roland van den Berghe. and philosophy are not just involved in a mutual relation with one another; they both depend on visible reality:

Alchemic processes are at play in Van den Berghe's work, transforming the experience of everyday life and elevating it to a spiritual-artistic level. The encounter which indisputably takes place in the work of our artist hetween temporal sublunary existence and spiritual utopian existence enables the viewer to see many cultural and religious connotations and patterns in this dialogue. The human urge and desire to rise above the valley of tears in which our actual existence is imprisoned has been a hallmark of Western art over the centuries.

Goethe expressed it in the following lines:

Ach! könnt'ich doch auf Bergeshöhn

In deinem lieben Lichte gehn,

Um Bergeshöhle mit Geistern schweben,

Auf Wiesen in deinem Dämmer weben,

Von allem Wissensqualm entladen

In deinem Tau gesund mich baden! (15)

What here finds expression is not the aching pining to escape from the suffering of existence or to deny our actual existence. It is rather the attempt to surrender to a luxuriant brilliance (and perhaps the religious sheen it contains) in order to approach and - in Goethe's words - to renew and improve the innermost human self. In Goethe's vision there is a subtle connection between concrete, temporal reality and the fleeting glimpse of eternity. The poet's desire has always been aimed at embodying the sublime spirit of being in the present (vergegenwartigen)(16).

Goethe's views on this subject are akin to those of classical Jewish mysticism, which distinguishes between ‘contact with God' and the mystical union. "In general Hebrew usage, 'devekut' only means attachement or devoutness. But since the thirteenth century it has been used by the mystics in the sense of close and most intimate communion with God", according te G. Scholem. He adds that this contact "is the last grade of ascent to God. It is not union, because union with God is denied to man even in that mystical upsurge of the soul, according to kabbalistic theology" (17).

Without being aware of it, Roland van den Berghe is faithfully following the path of Jewish mysticism or Kabbala. His Israel project shows a “meeting' of bubble and concrete reality, but no ‘unity' in a mystical sense. The mystical or religious facet of his work does not allow us to turn our back on our responsibility towards 'Haolam Haze' — the classical Hebrew term for this world. This has also been the path of Judaism since time immemorial.

Every “moment" contains a responsibility. But Van den Berghe measures this against an identifiable historical situation rather than in terms of the fleeting nature of time. A minuscule moment that represents the full weight of the temporal. These are the only kind of “moments', burdened with the heavy weight of events and experiences, with which people should reckon. This is the stage on which van den Berghe confronts temporal needs with dream and utopia. This is the only way he claims, for people be able to walk the tightrope stretched between absolute values and practical considerations, without falling prey to the security of an ‘immobile idea', as they proceed towards the peaks of human capacity and creativity (18).

The attempt to encompass these two domains of existence - the actual reality of history, and the utopian vision - drives Van den Berghe to look for a way of overcoming the alienation that is inherent in everyday life. He rejects every form of menacing institutionalisation or rigidity which suffocates the freedom of inner life. He tends to remain aloof from major state and social organisations from the cultural and religious establishment. He issues both himself and humanity a two-pronged challenge: to remain in touch with the roots of existence, with the innermost spiritual notions, religious dreams or forms of hope; and at the same time to transform the forces which are nourished by these roots into creative and artistic work.

The experiential world of Van den Berghe is threatened by the tension which results from the two characteristic poles of his personality. A life as an anarchist and as a reformer with a developed sense of social responsibility means in practice that one is constantly tossed back and forth between these two poles. His anarchism is not devoid of a certain tragic dimension, perhaps symbolised in the biblical figure of Job, the paragon of all those who have to suffer. The tragicomical dimension which is also a component of his anarchism is more related to the figure of Don Quixote.

The sharp duality which is rooted in the heart of his personal life is not so different from the rift between the “eternal commandment’ and the ‘voice of the present which Martin Buber has described as the source on which the "true poet' draws and which gives birth to true art:" The imperative of the spirit is discernable only in so far as we are able to encode its meaning, time and again, against the context of changing historical situations. (....only in so far as) we are able to be attuned, simul- taneously, to the voice of the eternal imperative and tao the voice of the present...

The very first phenomenon which enables the birth of those rare creatures known as poetry or songs occur in the soul of man, in the engaging exchange there is between "moment' and "eternity". The poet must be able to receive both signals into his aching heart and to await the moment of meeting: he has to accept the alluring invitation of the impermeable, dim shadows of eternity yet at the same time welcome the stark and naked bright light of the moment. From the fraction of interaction between them, a real poem is born. (19)

There is a correspondence between the dialogue which consumes Van den Berghe's poetic soul and Buber's penetrating observations on the act of creation. The Israel project expresses in an extraordinary manner the persistent tension which exists between the hard reality of life and the supernatural sources of beauty and belief.

In the West, images of and emotional responses to the land of Israel are derived from the rich sources of the Judaeo-Christian tradition. It is as if the pure blue of the sky above Israel evokes a unique spirituality. Nietzsche said: "Prophets could rise under the blue skies of Judea and Jerusalem and not beneath the skies of Europe, which are filled with the fumes of alcohol and the smoke clouds of pipes." But the sky of the Holy Land is not enough for Van den Berghe. He brings about an interaction the bubble and the sky, and between the bubble and earthly life.

An aura of spirituality and holiness surrounds the images of the ‘Heavenly Jerusalem', permeating not only the firmament above but also the landscape itself. However today — as always — there is a concrete reality too. This the product of the struggle which human beings had to wage with the land, and is connected with their existential needs and concerns. This aspect of Israel has always been linked with a "Worldly Jerusalem' — the city of flesh and blood, bricks and mortar.

Still, the truth is that the country is inhabited by both Jerusalems, that each Jerusalem is sustained by the other, that they both compete for human, particularly artistic, attention. Although the spirit of the heavenly and eternal city is diametrically opposed to the sublunary and temporal city, they complement one another. They both serve as a vanishing point for human endeavour — one binds people to the domain of tangible objects, the other elevates them to the domain of the promise. In the artistic representation of the Israeli landscape by Van den Berghe one can see the reflection of both the firm links with the tangible and the soaring flight of hope.

The bubble — the most striking hallmark of the Israel project — is transparent and colourful. It reflects tha light and shadow of the surrounding space. Its mode of existence is both transitory and captivating. It is born and dies in a flash. But caught in the lens of the artist’'s camera, it becomes ageless and as such it is a central component of the work of art. The fleeting elements, in other words all the heavenly, bewitching, utopian or dreamlike twinkles caught in the bubble, are not just frozen, but they also merge with the representation of a tangible nature. They are absorbed by it, enrich it with a spiritual quality, and perhaps confer on it a touch of the sacred or religious. The bubble is a symbol of spiritual beauty, even of the supernatural that is always only knowable as a moment of mercy, a touch, a glow or a profound sensation. After it has gone it leaves no trace or impression behind. Roland van den Berghe challenges this vanishing — his aim is to capture and hold on to the magic or the ecstasy of the dream, the beauty of the vision.

In the light of his urge to decipher the vision of Israel. Van den Berghe had no choice but to engage in a direct confrontation with the country. He would never be able to solve this riddle from the 'prison' of his atelier. What he felt inspired to do as an artist — to come into contact with the country in a unique way — could only be achieved within its material and spiritual manifestation. He did not come to Israel as a tourist or a pilgrim, but as an artist. His attempt to engage in dialogue with the object of his quest — a dialogue with the soil, the landscape and the population — was not just a success, but outstripped all expectations. He successfully managed to overcome a schizophrenic rupture between the artist who is searching for himself and the responsibility of someone who expresses his sense of dedication and commitment through the pleasure of giving. The achievement of a feat of this kind is by no means easy, and it is never accomplished once and for all. Time and again the artist has to make an effort in order to attain this delicate balance.

Roland van den Berghe is not the only one to have used the idea of bubbles in art as a means of expression. All the same, comparison of the way in which he has used the bubble with that of other artists reveals a striking contrast. Bubbles are also to be found in the work of the well-known Israeli artist Yossl Bergner (Vienna 1920-) from the 1960s. The viewer is given the impression t the form in which these bubbles appear undergoes a metamorphosis: sometimes they resemble small glass spheres — perhaps marbles — and at the same time these bubbles look like the tears on a young girl's cheek. In Bergner's painting ‘Morning in Jaffa', these bubbles turn out to be tears which well up in silence from the crevice of a dilapidated house without windows. The famous dramatist and writer Nissim Aloni, who is with as an interpreter of Bergner's work, describes these bubbles as ‘shining marbles, frozen to a virgin's cheek (20)." On the basis of Aloni's interpretation, we can suppose that the marbles or bubbles are a reflection of the way in which the artist has conceived Jewish mysticism. This enables him to evade the Jewish prohibition that obliges the artist to freeze the eternal flow of the world in colour (21).

We are now in a position to demonstrate that each of the two artists has used the bubble in a very different way: while the eternal, hidden and dynamic vitality of the world — and of life — is enclosed and frozen in Bergner's bubbles, Roland van den Berghe constantly brings this quality back to life in his bubbles i 1 and reinforce its perpetual interac existence. In Van den Berghe's work, the bubble the ongoing dialogue that is conducted between moment eternity, and it is this exchange which is his prime artistic and philosophical concern. The artist tries to achieve a fusion of the temporal and the eternal, and the bubble is the place where this situation is brought about (22). And although this fusion is bound to be as elusive and fragile as a bubble, Van den Berghe's bubble seems to risk its own vulnerability as if assuming the form of something eternal. Perhaps the artist wanted his bubbles to remind us of those elements of eternity which are latent in the temporal, awaiting the moment when they are discovered by humanity and integrated in its utopian vision.

The framed images of the Israeli landscape as they are seen through the transparent bubbles rivet the viewers gaze on an unusual aspect. The viewer is expected to wonder what the purpose and meaning of the bubbles. The images are only a ‘background' for the most important element: the appearance of the bubble on a familiar stage. “The bubble without landscape', says Van den Berghe, “would be like an opera singer without a voice.'

What role do utopias, dreams and visions play in human lives? It is a fact that this has been a central problam for the arts through the ages. The same is trues of Roland van den Berghe and — as far as he is concerned — for the viewers of his work too. It emerges in the work of Rainer Maria Rilke as a dominant theme. Rilke has often spoken of the sharp tension between people's utopian geals znd the routine of existence which weighs them down after the loss of their youth. Rilke:

(...) Ist es möglich, denkt es, dass man noch nichts Wirkliches und Wichtiges gesehen, erkannt und gesagt hat? Ist es möglich, dass man Jahrtausende Zeit gehabt hat, zu schauen, nachzudenken und aufzuzeichnen, und dass man die Jahrtausende hat vergehen lassen wie eine Schulpause, in der man sein Butterbrot isst und einen Apfel?

Ja, es ist möglich.

Ist es möglich, dass man trotz Erfindungen und Fortschritten, trotz Kultur, Religion und welweisheit an der Oberfliche, die doch immerhin etwas gewesen wäre, mit einem unglaublich langweiligen Stoff überzogen hat, so dass sie aussieht, wie die Salonmöbel in den Sommerferien?

Ja, es ist möglich.(...) (23).

Roland van den Berghe's refusal to make concessions to routines or demands which everyday existence imposes and the alertness with which he resists the force of gravity of the concrete, external crust of life are both expres in the idea of the bubble. The bubble thus stands for desire to pass from the temporal to the eternal, from the historical and material plane of life to a transcendent level beyond place and time. It should be added in this connection that Van den Berghe's attitude should not be confused with a purely religious approach, although there are religious overtones in the full range of his universe. These overtones resonate and vibrate in the spiritual world of his person, as they do in Western culture, above all in art. The ‘Holy Virgin' is one of the themes which are echoed in this work (24).

The interpretation of this theme that Roland van den Berghe provides in his combined role as thinker and artist deserves a broader and more profound discussion in a different context (25). Nevertheless, we will here refer to a single point: the question at stake here concerns the representatlon of reality — one of the major issues modern art (26).

The way in which the nature of art is conceived is profoundly influenced by the development of photography and particularly of film in the modern era. In his 1936 essay on "The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction", Walter Benjamin discusses the question of whether the invention of the camera, which makes an original work of art endlessly reproducible, has not entirely transformed the character of art (27).

In the past art always stood for the unique, the original or the singular. It was enshrouded in mystery and had a religious dimension. In medieval Europe and in ancient tribal cultures it often served as an object of ritual and ceremony. It is only in the nineteenth century that visual art breaks away completely from religion and comes to exist autonomously. The most revolutionary changes which have taken place in the art of the modern world were the result of the invention of all kinds of mass reproduction, such as photography, film, gramophone records, cassettes, etc. These new methods of reproduction delivered a fatal blow to what Benjamin referred to in his essay as the special 'aura' of traditional art. He means by this term, that the work of art has cultural and religious connotations by which it's originality is not called into question, two characteristics which are connected with the function of the work of art in society. In the modern era art is no more than one of the many profane utilities.

This background reveals a new dimension in Van den Berghe's Israel project. It looks a profocation, an open refutation of Walter Benjamin's views.(28). After all, it is quite feasible to reproduce Van den Bergh's works of art. But at the same time they are permeated by an ‘aura' which, as in the case of medieval and Renaissance art, contains many religious, mystical and ritual elements. And it is above all the bubble with its many facets, layers of meaning and connotations which confers an ‘aura' on the work of art. (29)

We have come to the end: without an understanding of the numerous implications of the bubble - and my discussion of a few of them here is by no means comprehensive - it is impossible to understand the meaning of Roland van den Berghe's artistic idiom.

The secret of the vitality which operates in his art lies in the tension between what it explicitly puts on view and what forms its implicit message. Van den Berghe's work reveals his constant dissatisfaction with an existence which fails to transcend the limitations of here and now, and it also expresses his persistent desire for new, wider horizons. His art issues an urgent call to all humanity to reflect, to descend into their inner depths and to look there for a hidden dream, what once was a vision... but is now something neglected and forgotten. He aims for a widening of human consciousness, for a humanity that is better equipped to understand the world because it has other resources at its disposal beside the limited instruments of social and political insights.

Van den Berghe's world embraces a keen awareness of the existential crisis which is gripping the West today. In itself, that would hardly be sufficient as a breeding-ground for a project as visionary as his art is. But his inner life is also connected with the sources of power inspiration which have sustained Western civilisaticn (which led him, for example, to go in search of the many associations and connotations which are attached to ths shapes and contours of the Holy Land), and with ths utopian and visionary sources which sustgin this civilisation and maintain its vitality (39).

Thus the present is just a starting point for Van den Berghe, the point from which he seeks in the present for those patterns which are always capable of referring to the horizon of the future. There is no place for despair in art. Rather, it is an unequivocal summons to act and to assume responsibility towards the earth and the ‘family of man' which lives there.

See Jean Leering, "Roland Van den Berghe; Abatur - het in zichzelf besloten oog"TM in Artefactum, 44/92, 8.

See Barbara Reise "'Incredible' Belgium: impressions by Barbara Reise" - Studio International (1974).

See Wouter Kotte, Roland Van den Berghe: Impartial Ar- tist, catalogue of a one man show at the Museum for Contempory Art (Utrecht 1974).

See Tony and Rhoda Lederer, "World Bridge Olympiad 1974", Bridge bulletin No. 6 (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain). For more information about the back- grounds of this project see Hugues C. Boekraad "Orde scheppen in een niemandsland - een gesprek met Roland Van den Berghe"” in: Viet Nam/Cultuur/Biopolitiek, Te Elfder Ure 30 (1981), 90-100.

See Paul Hefting, "Metamorphoses of an Art Instrument - notes on the Otterlo Project of the artist Roland Van den Berghe", translated and edited by The Pentonville Gallery (London 1983). First published in Dutch in Te Elder Ure nr. 24 - Ideologietheorie nr 1 (1977).

See Willem Elias, "Ceci n'est pas une photo"; first published in Dutch in Nieuw Tijdschrift van de Vriie Universiteit Brussel, 3/3 (1990).

See also Hugues C. Boekraad, "Orde scheppen in een nie- mandsland”, and Roland Van den Berghe, "Holland-Halan, kaartleesritten", Te Elfder Ure nr. 30 - Viet Nam/ Cultuur/ Biopolitiek (Nijmegen 1981).

See M. Buber, "Elements of the Interhuman" (1953), The Knowledge of Man (New York 1965), p. 81. Idem, "Bergson's Concept of Intuition" (1943), Pointing the Way (New York, 1957), p. 81 See ibid, p. 84.

See ibid, p. 84.

See "Translator's Introduction" in: Michel Foucault, This Is Not a Pipe. Translated and Edited by J. Harkness (University of california press 1983), p. 3.

- See M. Foucault, This is not a Pipe, Translated and Edited by J. Harkness (University of California press 1983) pp. 15-54. The apparently didactic, pedantic character of the statement "This is not a pipe' explodes when it is connected with the colloquial meaning of the term “pipe': ‘cunt'. Humour thus foregrounds a different layer of meaning between the representation and its user, which was a constituent part of the painting. The viewer who tries to get to the bottom of it will discover that it was planned by the artist, Magritte. The artist evidently had a strategy to recruit viewers and to transform this recruitment into an accord.

- There is an interesting parallel between the integration in Van den Berghe's art and the way in which Eldert Willems has conceived the relation between poetic perceptions and philosophical insights. See Eldert Willems, Arph - kunstfilosofische onderzoekingen, The Peter de Ridder Press (The Netherlands 1978).

- See Goethe, Faust (Frankfurt a.M. 1974), p. 28 17. 18, 19. 20. 21 220

- See Karl Lowith, Von Hegel zu Nietzsche (Stuttgart 1953), p. 230. And compare Z. Levy, The Precursor of Jewish Existentialism - The Philosophy of F. Rosenzweig and its relationship to Hegel's system [in Hebrew] (Tel Aviv 1969), p. 107.

- See G. Scholem, "Devekut or Communion with God", The Messianic Idea in Judaism (New York 1971), p. 203.

See A.N. Whitehead, The Aims of Education (New York 1929), p. 10. And compare Max Daddushin's discussion of value concepts in society.

See Max Kaddushin, The Organic Thinking (New York 1938); 3rd ed. 1972) The Rabbinic Mind (New York,

See M. Buber, "On Eternity [in Hebrew] (Tel Aviv and the 1992), pp. 125-126

See introduction to Yossl Bergner - painting 1963-1968 [in Hebrew] (Jerusalem 1969), p. 12. Idem, idem.

See also Y. Fischer, "Reaction to Modernism", Ariel - A Review of Arts and Sciences in Israel no. 11 (Jerusalem 1965), pp. 16-21

The concept of "the eternal in the temporal" was coined by A.D. Gordon (1856-1922) who was one of the most important Jewish thinkers and men of spirit in the 20th century.

- See R.M. Rilke, Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Lauridge Brigge (Frankfurt a.M. 1982), p.23. And see also Paul Verlaine's poem "Resignation” - Poémes Saturniens, Oeu- vres Poétigues (Paris 1969), p. 26. 24.

- See Clarissa W. Etkinson, The Oldest Vocation - Christian Motherhood in the Middle Ages (Ithaca 1991), especially chapter one: "Christian Motherhood: Who Is My Mother?", pp. 1-15. This point takes on even broader connotations when related to the issue of the corporeality of Jesus which was also a complicated, controversial issue occupy- ing Western culture througout the ages. See also Marina Warner, Alone of all her sex: the myth and the cult of the Virgin Mary (London 1976). On this matter see D. Stern, "Imitatio Hominis: Anthropomorphism and the Cha- racter(s) of God in Rabbinic Literature", Prooftexts 12 (The John Hopkins University Press 1992), pp. 151-174 Compare, Gedaliahu G. Stroumsa, "Form(s) of God: Some Notes on Metatron and Christ," Harvard Theological Review 76/3 (1983), pp. 269-288; Michael Fishbane, "Some Forms of Divine Appearance in Ancient Jewish Thought", in From Ancient Israel to Modern Judaism: Intellect in Quest of Understanding, ed. J. Neusner, E.S. Frerichs, and N.M. Sarna, 2 Vols. (Atlanta 1989), Vol. 2, pp. 261-270.

- See G. von Wright, Explanation and Understanding (Ithaca 1971); H.G. Gadamer Truth and Method (New York 1975); M. Fishbane, "Hermeneutics”, in Contemporary Jewish Religi- ous Thought, edited by A.A. Cohen and P. Mendes-Flohr (New York 1987), pp. 353-361, and compare M. Fishbane, The Garments of Torah (Indiana University Press 1988).

- See for example, Gombrich's conception of the representa- tion of reality in modern painting: E.H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion (Princeton 1969). Compare Gombrich's views on the representation of reality in modern painting;...

- Walter Benjamin, "Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner Technischen Reproduzierbarkeit", Gesammelte Schriften, Band 1,2 (Frankfurt a.M. 1974), pp.431-508.

Walter Benjamin, IIluminations. Essays and Reflections, edited and with an introduction by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, New York, 1968. - G. Scholem, who was one of Benjamin's closest friends, discusses and criticises both his views on the reproduction of art in the modern era and the meaning Benjamin attached to the term ‘aura'. Incidentally, Scholem emphasises different facets of the guestion than the ones under discussion here. 29, 30. See G. Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friends- hip (Philadelphia 1981), pp. 199-202, 207. Compare Max Ernst's artistic hermeneutics to traditional aura in his work "The Blessed Virgin Chastising the Child esus Before Three WitnessesTM (1926). In J.-P. Sartre's last interview, published in the Nouvel Observateur in February 1980, he said that he could cope with life and that he “held on to it' thanks to hope. He would even look death in the eyes, when it came, as a man filled with hope, as someone who regards this idea as essential for human survival. But hope too must be planted and nurtured if it is to root among human beings. ‘The present world is terrible', Sartre said, “but it is only one moment in the long developmental process of history. And one of the driving forces behind every revolution has always been hope.' This credo could also be seen to be characteristic of the vision and art of Roland van den Berghe.

- GAZA -HET WANNEN -LE UANNAGE -THE WINNOWING UITRINE #114 - ROLAND UAN DEN BERGHE 8411 -26.11.2613 LUCA BIBLIOTHEEK SINT-LUKAS -PALEIZENSTRAAT 70 -1830 BRUSSEL MAANDAG-DONDERDAG B3:68-19:88 -URIJDAG 85:00-17.60